The First Slave Trade Act —1794

On March 22, 1794 the Third Congress passed the first Federal legislation dealing with the slave trade. Applying only to the international, not domestic trade, it prohibited United States citizens and residents from fitting out vessels intended for the foreign slave trade or to buy and sell slaves at foreign ports. Violators were subject to seizure of their vessels as well as a fine of $2,000 plus an additional $200 per slave.2

While the costs of violations were steep, the law did little to stem the trade. Owners could choose from a variety of subterfuges to disguise the purpose of voyages. Using sympathetic customs officials, forging ship’s papers, crewing vessels with Americans but sailing under foreign flags, and selling vessels in the West Indies to avoid returning to American ports were all used at one time or another to circumvent the law.

The only enforcement mechanism was for citizens to observe the off loading of slaves at foreign ports — typically in the West Indies — and causing suits to be brought in the Federal Court at the vessel’s home port where, upon return, it could be seized and condemned. Unfortunately, the home ports of these vessels often proved to be unwelcome jurisdictions for such suits. Ships condemned and auctioned were often sold back to the original owners at a bargain price when no other bidders materialized, there being a tacit understanding among the locals that they should stay away. To counter this, the Federal Government authorized court clerks to bid on the government’s behalf. Brazenly, in 1799, owners of the Lucy, of Bristol R.I., arranged for the kidnapping of a customs official on the day of the auction to prevent a competing bid.3 It would take war with France to provide the U.S. with a different way to enforce the law — at sea.

In 1794, enforcing U.S. law by interdicting the slave trade at sea was not an option. The Unites States had no ocean-going Navy and a small complement of revenue cutters. As we shall see, in 1798 the French finally provided the motivation for the United States to create one for self-defense. American warships put to sea in 1798 with the primary mission of defending American merchant vessels from French privateers, but also could report any violations of the 1794 act they observed while on patrol. The Navy would forward these reports to the Treasury Department who would, in turn, alert the pertinent federal revenue authorities who could then take action when a vessel returned to its home port.

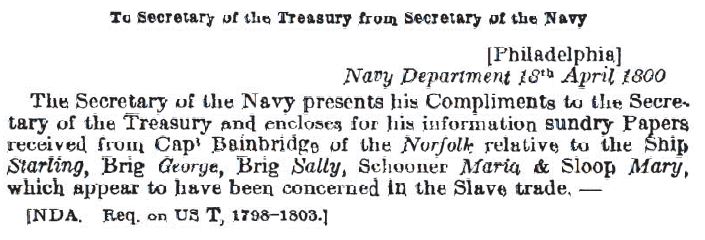

For example, in early 1799, Capt. William Bainbridge of the brig Norfolk sent a list of 5 slaving vessels to Navy Secretary Stoddert who duly passed it on to Treasury Secretary Wolcott. It’s not clear if any legal action resulted from the report however.4

The Amended Slave Trade Act — 1800

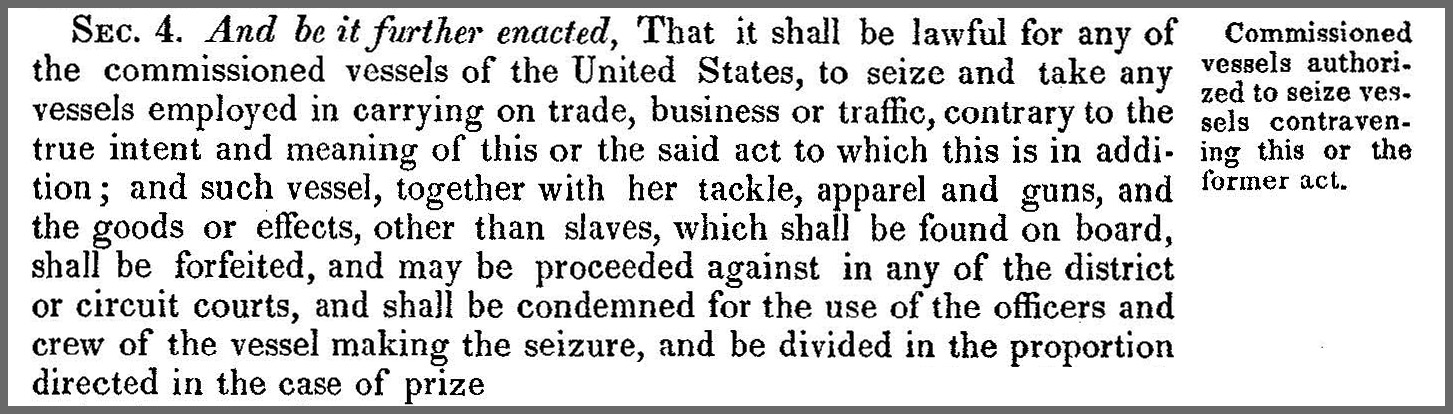

The legal situation changed significantly in May 1800, when Congress strengthened the 1794 Slave Trade Act. It increased penalties, closed loopholes and, most important for our story, authorized “any of the commissioned vessels of the United States to seize and take any vessels employed” contrary to the Act. The legal stage was set for what was to come and the Navy immediately got to work.5

Origins of the Amended Act

It is with some degree of irony to realize that the amended slave trade law wasn’t simply the result of Congressional activism, but rather, perhaps unexpectedly, from the activism of the free black community of Philadelphia.

In December 1799, Reverend Absalom Jones and 70 other “People of Colour, Freemen within the City and Suburbs of Philadelphia”, including Reverend Richard Allen, petitioned the United States Government for three things:

- To address deficiencies in the existing slave trade law (1794)

- To address deficiencies in the Fugitive Slave Law (1793)

- To “exert every means in your power to undo the heavy burdens, and prepare way for the oppressed to go free, that every yoke may, be broken.”

6The National Park Service has published a full copy and transcription of the petition online.7 Unfortunately, the accompanying discussion is incorrect when it asserts that, on January 2, 1800, “The petition … ultimately was denied approval.” The 85-1 “No” vote ONLY related to the third point in the petition. The one “yes” vote coming from George Thatcher who received a well-known written thank you from Absalom Jones. However, the first and second points listed above WERE referred to committee, leading to the amendment of the slave trade law AND, for the first time, establishing the right of free blacks to petition the government under the Constitution. See “A ‘class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies,” for a thorough discussion of the importance of this and other petitions.8

Congressman Joseph Waln of Pennsylvania, introduced the petition to the House on January 2, 1800 to acrimonious debate, with southern supporters arguing that the entire petition should be thrown out. All but one of the representatives agreed that consideration of the third request was in violation of the Constitution,9 but as we noted above, the remaining two were referred to committee for consideration. While dropping any proposed changes to the Fugitive Slave act, the committee did return the slave trade amendment which — followed by “a long and warm debate” — passed on May 3 by a vote of 67-5.10

John Rutledge Jr of South Carolina, who cast one of the five negative votes, argued that if slaving vessels were captured, northern states — where the former captives would likely be taken — were incapable of accepting the recently enslaved into their communities:11

What will become of them when landed? Who will feed them because they are hungry? Who will cloath them because they are naked, and who will take them in because they are strangers?

Indeed, this entire website provides the answers to these questions.

- Richard Peters Esq. ed., Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, (Boston, Little and Brown, 1845), II:70. Available online. ↩︎

- Ibid. I:348. Available online. ↩︎

- Cynthia Mestad Johnson, James Dewolf and the Rhode Island Slave Trade (Charleston, SC, History Press, 2014), pp 75–82. Pertinent clips from the book are available online at Google Books (accessed April 26, 2019). ↩︎

- Office of Naval Records and Library, Naval documents related to the quasi-war between the United States and France & Naval Operations From January 1800 to May 1800, Washington : U.S. G.P.O., 1938. Vol. 4, p. 426. The Norfolk had arrived in Philadelphia from Havana on April 12, 1800.

↩︎ - Public Statutes, II:70. ↩︎

- Ironically, this same misstatement is repeated on one of the placards removed from the Presidents’ House Memorial in Philadelphia by the National Park Service in January, 2026. ↩︎

- Absalom Jones et. al, “The Petition of the People of Colour, Freemen within the City, and Suburbs of Philadelphia”, 1799. Online, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/inde-1799-12-30-petition-ajones-abolition-guinea.htm , accessed 19 January 2026. ↩︎

- Nicholas P. Wood, “A ‘class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies,” William and Mary Quarterly 74 (January 2017). ↩︎

- Congress was very sensitive to any suggestion that they might be in violation of the Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 of the Constitution which prohibited it from enacting any legislation prohibiting slave imports until 1808 (even if they were only debating it). Note that in 1800, every STATE had laws prohibiting slave imports into their jurisdictions, but that the Federal government did and could not. ↩︎

- “Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States, Sixth Congress”, 10: 699 (Washington, Gales and Seaton, 1851). Available online. Only a short summary of the debate is published here, but more complete transcriptions were sometimes published in newspapers. See below. ↩︎

- “Debate on the Slave Trade”, The Universal Gazette, Thursday, May 29, 1800, Philadelphia, PA, Vol:II, Issue:CXXXIII, Page:2. The full text of the debate can be found here. ↩︎