It seems that my commitment to provide yearly updates on the project has fallen behind schedule by a year once again. Nonetheless, I am pleased to report that the work continues, albeit at a slower pace than I might have wanted. Here, I will summarize some recent work in the hope that I will be able to complete and incorporate it into the main website in the future.

To begin, I’d like to point out that this coming Monday, August 4, 2025 marks the 225th anniversary of the arrival of the slaving schooner Phoebe at the Fort Mifflin quarantine station, Philadelphia (above), with the Prudent arriving two days later. These arrivals mark the beginning of the Ganges story in Philadelphia, a story that continues to this day through the Ganges descendants living in the area.

The Origins of the Amended Slave Trade Law (1800)

While the focus of my research over the years has been the Ganges Africans themselves, I have tried not to neglect the circumstances that brought them to Philadelphia in the first place. One key element was the amended law (May 1800), “An Act in addition to the act intituled [sic] ‘An act to prohibit the carrying of the Slave Trade from the United States to any foreign place or country'” which provided the statutory authority to Captain Mullowney and the USS Ganges to interdict the voyages of the Prudent and Phoebe (See The Law for more detail). What I hadn’t realized until recently, was that the law’s amendation was the direct result of political action by the free black community of Philadelphia.

In December 1799, Reverend Absalom Jones and 70 other “People of Colour, Freemen within the City and Suburbs of Philadelphia”, including Reverend Richard Allen, petitioned the United States Government for three things [1]:

- To address deficiencies in the existing slave trade law (1794)

- To address deficiencies in the Fugitive Slave Law (1793)

- To “exert every means in your power to undo the heavy burdens, and prepare way for the oppressed to go free, that every yoke may, be broken.”

Congressman Robert Waln of Pennsylvania, introduced the petition to the House on January 2, 1800 to acrimonious debate, with southern supporters arguing that the entire petition should be thrown out. All but one of the representatives agreed that consideration of the third request was in violation of the Constitution [2], but the remaining two were referred to committee for consideration. While dropping any proposed changes to the Fugitive Slave act, the committee did return the slave trade amendment as described here, which — followed by “a long and warm debate” — passed on May 3 by a vote of 67-5. [3]

John Rutledge Jr of South Carolina, who cast one of the five negative votes, had argued that if slaving vessels were captured, northern states — where the former captives would likely be taken — were incapable of accepting the recently enslaved into their communities:

What will become of them when landed? Who will feed them because they are hungry? Who will cloath them because they are naked, and who will take them in because they are strangers? [4]

Indeed, this entire website provides many of the answers to these questions, but how was it done?

The Network

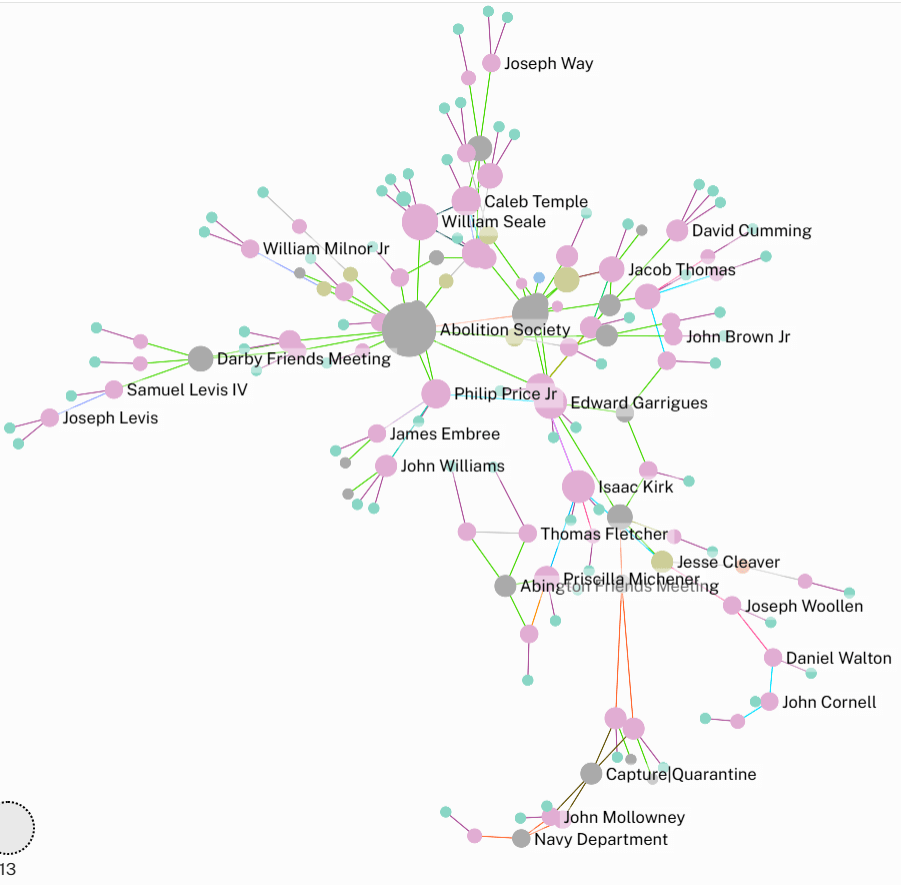

The network diagram was created using Gephi, then rendered for the web using Retina.

We know that the PAS organized the effort to indenture the Ganges Africans, but this begs the question of how they were able to pull it off. As I pointed out in the Indentures Section, the committee of guardians typically sponsored “only” a few indentures per month and the fact that their special committee managed to place more than 100 of the Ganges Africans over a period of 2 months indicates that a large scale, concerted effort was needed. It’s easy enough to hypothesize that Society members called on friends, family and neighbors, but was this really the case?

I’ve spend a considerable amount of time over the last year investigating this question and, although the work remains incomplete, I can still provide a qualified answer as “yes”. For example, Samuel Bettle, the chair of the PAS’s special committee, had strong family ties to the Brandywine Valley through his fiancé and future wife, Jane Temple, whose brothers, Caleb and Edward Temple, indentured John and Samuel Ganges. By using published family trees, it’s possible to identify many family links among the Ganges masters, especially through their spouses, indicating indirectly, the presence and influence of women in the network. The masters shared other connections, often via common church membership, particularly, but not exclusively, Quaker, as well associations through the Philadelphia Health Office, the US Navy and, of course, the Abolition Society.

This visualization of the network, though incomplete and in rough form, still clearly pictures the central role played by the Abolition Society and helps us identify individuals who played significant and multiple roles in the network: Philip Price Jr, Samuel Painter Jr., Edward Garrigues, Isaac Kirk, Jesse Trump and Priscilla Michener. I plan to flesh out the network in the coming months to provide a more complete picture as well as describing the methods I used to identify these links in a paper submitted (but not yet accepted) to the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.

Precedents

Finally, I’ve been trying to get a better sense of the context in which the Ganges incident took place by asking the following questions:

Q: Was the Ganges incident the first of its kind where enslaved Africans were freed under the US law banning US vessels from carrying slaves to foreign ports?

A: No

A number of vessels were condemned and sold under the original, 1794 anti-slave trade law, but only after they had discharged their human cargo overseas and returned to their home ports in the United States — with one exception. On December 3, 1796, the Brig Lady Waltersdorf arrived in Philadelphia, 30 days from St. Croix. She had cleared New York earlier in the year as an American vessel, but had conducted a slaving voyage to Africa and the West Indies by sailing under Danish colors. Most of her human cargo was discharged in the Caribbean, but the captain, Thomas “Beau” Walker, was reckless enough to bring two of his personal slaves with him. Soon thereafter, he was brought to the court of (who else) Judge Richard Peters. The Lady Waltersdorf was condemned and sold and Walker’s enslaved Africans, a man nick-named Bacchus and an unnamed woman, were liberated. Thus, Bacchus and the unknown woman hold the distinction of being the first enslaved Africans to be freed under the 1794 law.

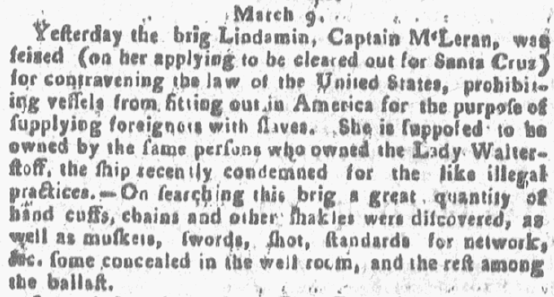

In a second reckless act — especially since he was still in Philadelphia — Walker fitted out a second vessel for the slave trade, the brig Lindeman. There was enough hidden evidence discovered on board that Walker was taken to Richard Peter’s court again. The Lindeman condemned and sold as well.

There is more of this story to tell, but that must wait for the next update. [3]

Q: Was the Ganges incident the first time where American slaving vessels were captured at sea by the USN under the amended law of May 1800?

A: No

This distinction belongs to the USS Experiment, Captain William Malley, which captured the Sloop Betsy off Cuba in June 1800. Unfortunately, the slaves aboard were not freed, but taken to Havana instead. You can read the details here, where I have documented the event in some detail.

Notes

[1] The National Park Service provides a full copy and transcription of the petition here. Unfortunately, the accompanying discussion is wrong when it asserts that, on January 2, 1800, “The petition … ultimately was denied approval.” The 85-1 “No” vote ONLY related to the third point in the petition. The one “yes” vote coming from George Thatcher who received a well-known written thank you from Absalom Jones. However, as I describe above, the first and second points WERE referred to the committee, leading to the amendment of the slave trade law AND, for the first time, establishing the right of free blacks to petition the government under the constitution. See also: Nicholas P. Wood, “A ‘class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies,” William and Mary Quarterly 74 (January 2017): 109-44 for a thorough discussion of the importance of this and other petitions.

[2] Congress was very sensitive to any suggestion that they might be in violation of the Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 of the Constitution which prohibited it from enacting any legislation prohibiting slave imports until 1808 (even if they were only debating it). Note that in 1800, every STATE had laws prohibiting slave imports into their jurisdictions, but that the Federal government did and could not.

[3] “Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States, Sixth Congress”, 10: 699 (Washington, Gales and Seaton, 1851). Available online.

[4] Thomas “Beau” Walker was an ancestor of the Presidents Bush. Perhaps trying to recoup his losses, he personally undertook yet another slaving voyage to Africa in 1797, but was murdered by his crew before its completion. Look here for a little more info.