Acknowledgement

Preparation of this profile for Furry/Curry Ganges would not have been possible without the thoughtful and patient assistance of Patricia Henry who died May 4th of this year[1]. Patricia provided me with insights and guidance to rare local sources, including the Hannah Walker Stephens Day Book[2], the Burial records of Valley Friends Meeting[3] and a key deed recital that ties Furry and Curry Ganges.[4] I will miss her expertise and counsel most acutely.

Genealogical Summary

If you don’t see the summary below, click on the link.

Discussion

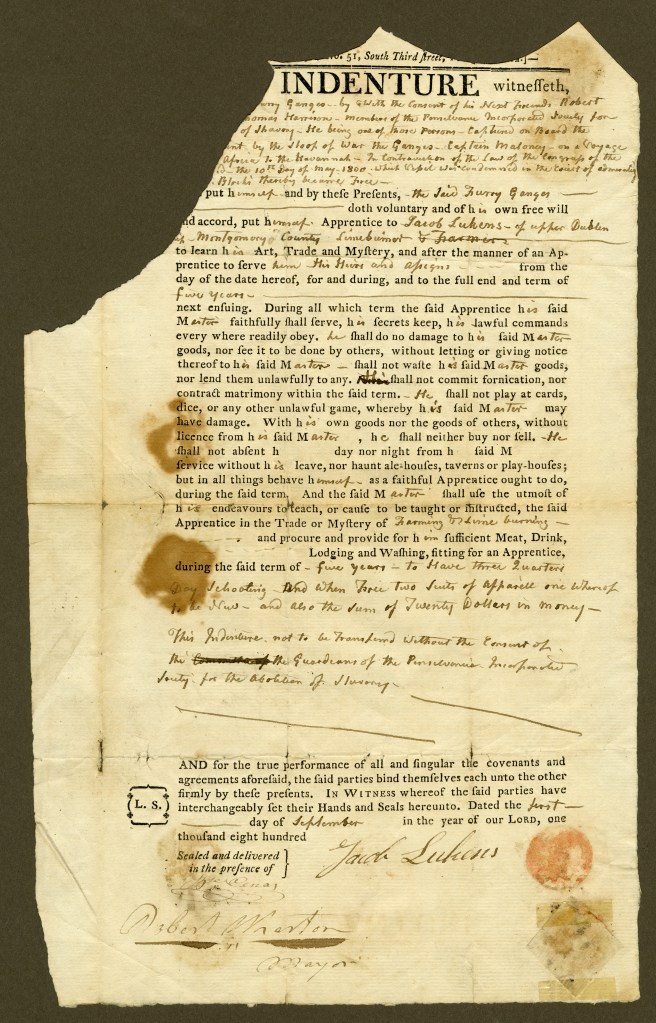

Furry [5] Ganges was among the seventeen enslaved Africans aboard the Prudent and, unlike the captives from the Phoebe, he was fully emancipated less than a month after after his arrival at the Fort Mifflin quarantine station. On September 1, signing with a mark, he indentured himself to Jacob Lukens of Upper Dublin to be “taught the Trade or Mystery” of farming and lime burning. Most of Ganges men were indentured simply as farmers, i.e. farm hands. This is one of the few instances where the master involved committed to teach beyond the “farm hand” baseline.[6]

Jacob Lukens gave his occupation as a farmer and lime burner and other records bear this out. He had inherited more than 100 acres in Upper Dublin from his father, Rynear in 1786 and he appears in the tax records until 1802, when he and his wife, Mary, apparently gave up active management of the property and removed first to Philadelphia, then Bristol and finally to Abington. Presumably leasing his inheritance for a few more years, Lukens eventually sold it off piece-wise in 1810-1811, including at least three small (about an acre) parcels which contained either lime quarries and/or kilns.[7]

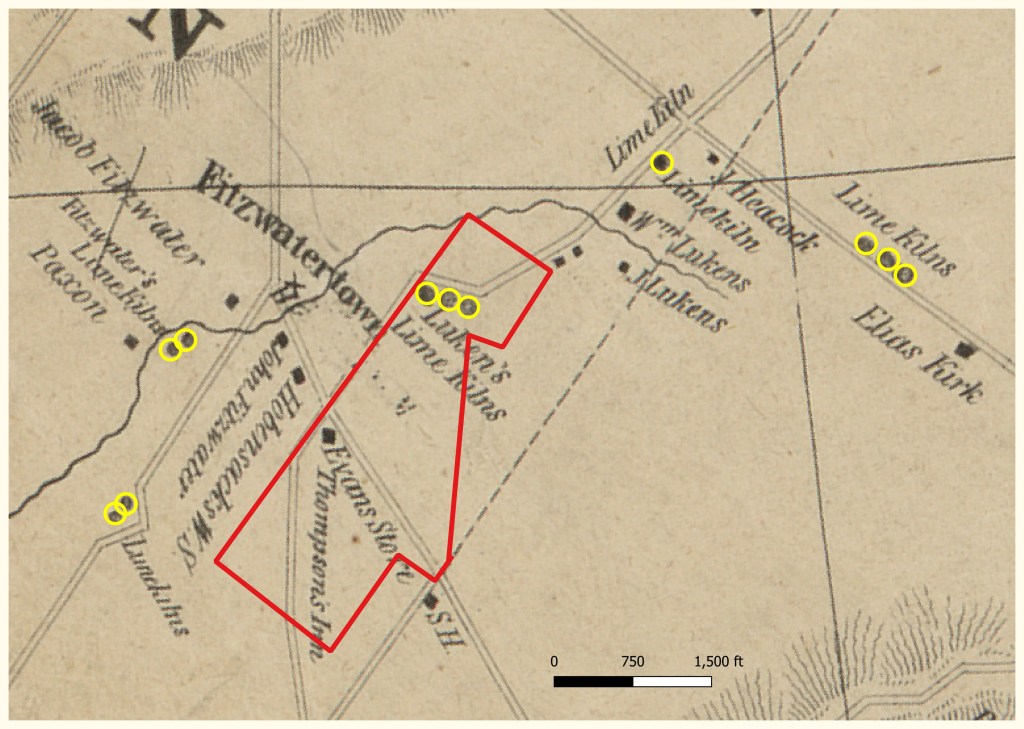

As late as 1849, local maps (below) show three lime kilns on what was Jacob Lukens’ property and another eight in the immediate vicinity. It is no surprise that the local road was dubbed “Limekiln Pike”.

We don’t know for sure whether Furry worked at the kilns nor whether he stayed to work in Upper Dublin after Jacob Lukens’ move or continued to live with the family until his indenture expired in 1805. In fact, we have not found any additional records beyond his indenture that refer to Furry by name. Of course, we have seen that it was not unusual for Ganges Africans to change their names all or in part, so Furry could have simply done that and carried on, leaving records as he went. From the original list of Ganges, there are several plausible, if not proven, candidates who could be Furry. Based on the available evidence gathered to-date, the most plausible candidate is Curry Ganges of Tredyffrin Township.

Are Furry and Curry Ganges the same man?

We find a man named Curry Ganges in the 1850 census for Tredyfffrin Township, Chester County. We can be reasonably certain that he was, in fact, one of the Ganges Africans. In addition to his surname, the census give his age as 55 and his birthplace as Africa. Later censuses of his children consistently give Curry’s birthplace as Africa, so this fact seems to have been well established in his family. [9]

Since there is no man named Curry among the Ganges indentured in 1800, we naturally assume that he changed it from something else. As we have seen in other cases, it was not unusual for Ganges Africans to change their names. Sometimes the case is well documented but in others we must rely on more indirect evidence to construct a plausible association.

Starting here, we can look for alternatives among the 85 surviving Ganges men based on their assigned name and location. There are three: Columbus the sole Ganges indentured to a master in Tredyffrin Township, Joseph Conrad (Conard); Carney and Furry whose names are similar to Curry and were living relatively close by ( West Whiteland, 10mi; Upper Dublin 20mi). [10]

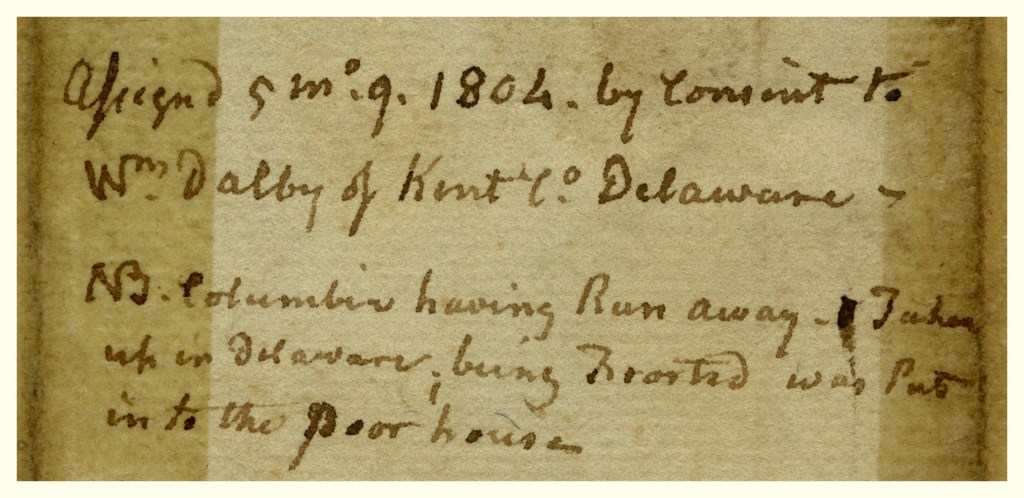

At first glance, Columbus seems to be the best choice , since Joseph Conard’s farm was only a mile or so from the four acre tract where Curry settled permanently. However, only a few months before his four year term expired, Columbus’ indenture was assigned to William Dalby of Kent County, Delaware. Presumably not liking this turn of affairs, Columbus ran away only to be captured and placed in the care of the Kent County poor house. It seems unlikely he would have returned to Pennsylvania. [11]

Aside from his indenture to Richard Thomas Esq. of West Whiteland, we have only a few records of Carney Ganges to go on. We find him working as a competent field hand and mill assistant on Thomas’ farm in 1800 &1801, but nothing beyond that. The Thomas family were Quakers, associated with the Goshen Meeting and, given the likelihood for Friends to intermarry, it is not surprising there are connections to Valley Friends, with which Curry had a long-term association. However, we currently lack additional evidence to support the case. [12]

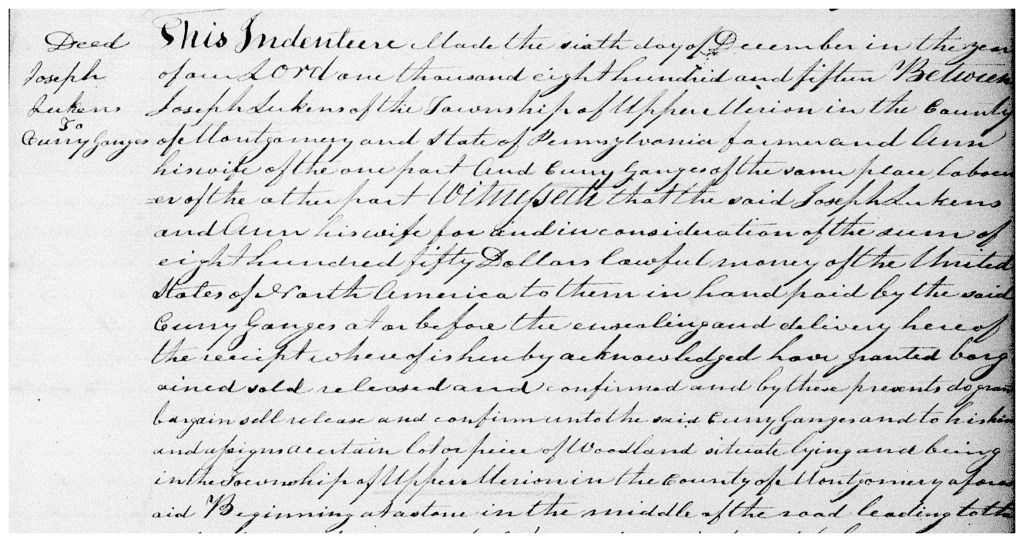

The case associating Furry with Curry is somewhat stronger. Of course, there’s the similarity of the names. Further, records indicate a double connection to the Lukens family: first, through Furry’s indenture to Jacob Lukens of Upper Dublin in 1800; second through Curry’s business dealings with Joseph Lukens of Upper Merion, Jacob’s first cousin, buying a small piece of land from him in 1815. [13] Further, Jacob was Quaker, providing direct connection to Valley Friends, where his cousin Joseph was a member.

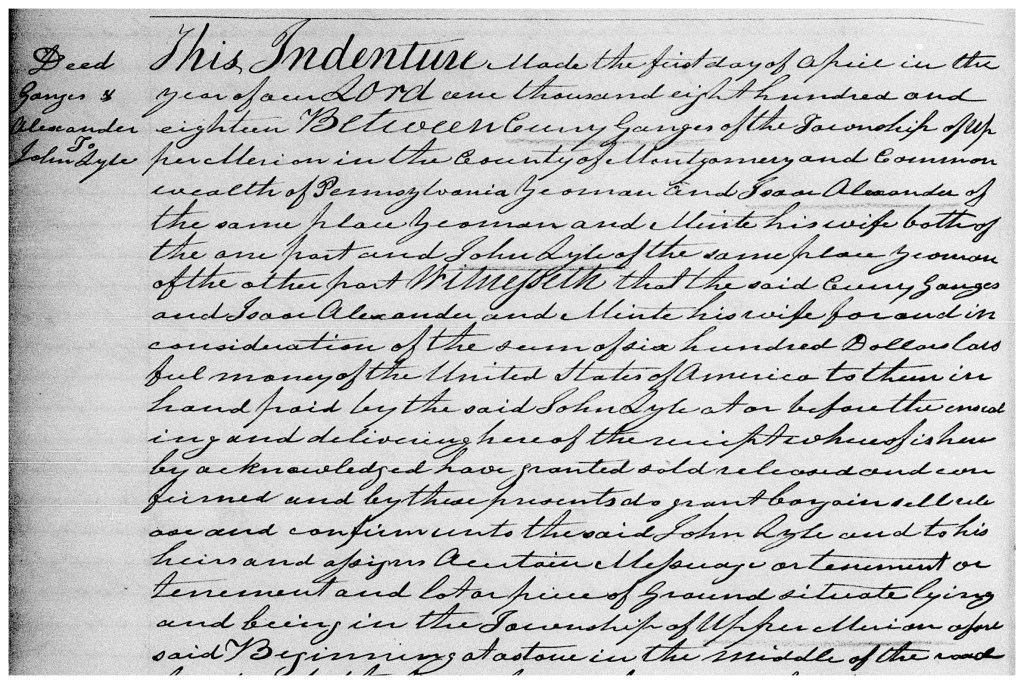

One additional record makes the case stronger. In another of Joseph Lukens’ land sales in 1818, Isaac Alexander purchased a four acre parcel immediately adjacent to Curry’s. The deed recital contains an important clue, reading as follows:

… North fifty eight degrees West nineteen perches and four tenths of a perch to a post thence by a Lot granted or intended to be granted to Curry Furgander [emphasis added] …

In the sections that follow we use the given name our subject chose, Curry, with the understanding that the association of him with Furry Ganges is a contingent one. Nonetheless, as we shall see, Furry or not, Curry Ganges’ story is one worth telling.

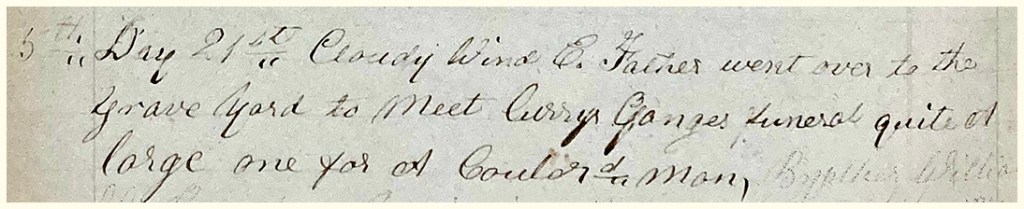

“Quite a Large Funeral for a Colored Man”

This is how Hannah Walker Stephens, wife of Stephen (“Father”, above), recorded the funeral of Curry Ganges at the Valley Friends Meeting in Tredyffrin Township. Had Curry been white, the size of his funeral might not have been cause for comment. After all, any man who had lived in the township for nearly 40 years, owned a house and property, paid his taxes, married and fathered thirteen children — five of whom he buried there — who regularly attended local schools, surely would have earned the respect of his neighbors — enough respect for them to devote an hour or two of their time on cloudy, windy October day to celebrate his life with his widow and surviving children.

What makes the story remarkable is that Curry Ganges was not only a colored man, but also a formerly enslaved African who arrived in Philadelphia with nothing, not even the “clothes on his back.” Yet, unlike many of his shipmates, he was able to accumulate enough property so his history could be reconstructed using the primary sources typically used by family historians: census, land and tax records.

He earned the right to be a citizen of Tredyffrin and so it’s fair to interpret Stephen Stephens’ short homage to be as much an indicator of respect as of surprise.

Landowner

The first indication we have of Curry residing in the Tredyffrin area is his purchase of a four acre parcel of land in Upper Merion (just over the border from Tredyffrin, see the map below) from Joseph Lukens for $850. Even though Curry immediately sold an undivided half interest to Isaac Alexander for $425, it is still remarkable that he was able to garner sufficient financial resources in fifteen years to buy any land at all. Curry is among only a handful of the Ganges Africans who managed to do this. [13]

This begs the question of how?. We have no direct evidence one way or the other, but the timing suggests he may have been able to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by the War of 1812, either by performing critical labor or perhaps serving in the military or on a privateer. Given the respect shown him in later life, it may also be that he was able to gain the trust of his white neighbors that they were willing to advance him the funds, formally or informally. Or, perhaps the simplest explanation is best: that he was able to save the money he earned in the ten years after his indenture ended. We may never know for certain, but the fact remains he paid for and was the legal a legal co-owner of the property.

The First Lot

The deed preamble describes the parcel as “a lot or piece of woodland”. There is no indication that the land has any improvements. This suggests that Curry and his partner bought it to harvest its timber. In addition to heating, there was demand for cord wood to fire the local lime kilns and, perhaps, an opportunity for Curry to take advantage of his experience working for Jacob Lukens. Upper Merion township tax records for 1816-1818 show Isaac Alexander as the occupier of four acres, so it isn’t clear if Curry lived on the site at all. [14]

Curry and Isaac Alexander did not hold the lot for long. Less than three years later, they sold it, together with Isaac’s wife Minty, to John Lyle for $600, an apparent loss. [15] At the time, the United states was suffering an economic downturn and with work hard to come by it may have been necessary to sell, even at a loss, to cover living expenses. However, the parcel description changed under their ownership to “a certain messuage or tenement and lot or piece of ground,” indicating that a house now stood on the property, probably built by Isaac and/or Curry after clearing the trees and selling the wood. The tax assessments don’t reflect a building being added, so whatever was built was probably a modest effort.

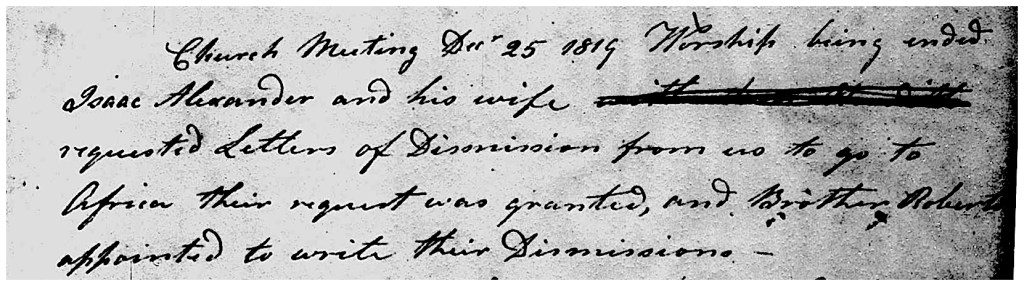

This deed also provides a key detail about Curry’s business partner, Isaac Alexander: his wife’s name, Minty. Because she would have a dower interest in the property, Pennsylvania law required her to be a party to the deed and consent to the sale. At about the same time, Isaac and Minty appear in the records of the Baptist Church of the Great Valley, being baptized in 1817 and 1818, respectively. Later, on Christmas Day 1819, the couple “requested letters of dismission from us [the Baptist church] to go to Africa. Their request was granted.”

This event sets an entire new chapter to the story in motion, for we find that Isaac, Minty and their two children set sail from New York a few weeks later, in early February, 1820, aboard the ship Elizabeth, bound for the coast of Africa.

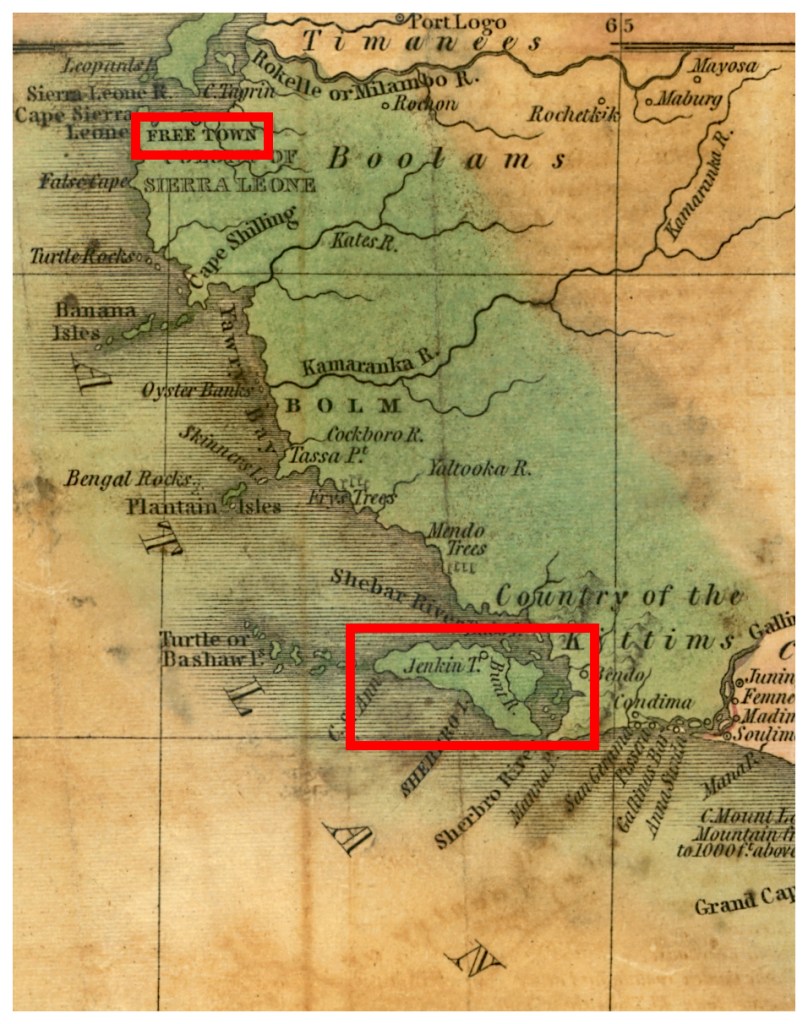

The Elizabeth’s voyage has the distinction of being the first organized by the American Colonization Society. Its mission was to repatriate free American blacks back to Africa. At the time the Elizabeth set sail, the Society didn’t even have a permanent place for their colonists to settle. This was left for the expedition’s leaders to work out upon arrival. Although the voyage was relatively uneventful, the colonists were forced to set up temporary quarters at a small settlement named Campelar on Sherbro Island fifty miles southeast of Freetown, Sierra Leone.. This proved to be disastrous for the new arrivals as the island was swampy and ridden with tropical diseases against which they had little natural immunity. Soon, Isaac and Minty’s two children were dead and, although the parents survived the initial wave of deaths. Isaac drowned in 1822 and Minty succumbed to “brain fever” in 1839. [17]

It is astonishing to consider the possibility that Isaac Alexander and/or Minty might be included among the Ganges Africans and that they had the opportunity to return home twenty years later. It would not have been all that unusual for them to drop their assigned names and take on more meaningful ones. They are also about the right age (at ages 29 and 25 respectively, both Isaac and Minty were born before 1800). Unfortunately, this is where the evidence trail ends, for now. But, even though we may never know for sure, Curry Ganges almost certainly knew of the opportunity the Colonization Society was presenting and chose, for whatever reasons, not to take advantage of it and stayed “at home.”

The Homestead

So, while business partner Isaac Alexander emigrated to West Africa, Curry Ganges chose to remain in the vicinity. In the1820 census, we find him in Tredyffrin as a free colored male head-of-household, aged 17-26, with his newly formed family: a free colored female 17-26 (probably his wife Rosanna), and a free colored male child under 14 (probably Curry’s first born, Peter, b. circa 1819.) The census enumeration also records a free colored male, aged over 45. We don’t know the identity of this man, but it might be Rosanna’s father or perhaps another of the Ganges Africans. We simply don’t know for certain. The census describes Curry’s work as being “manufacture”, not agriculture as we might expect. This is consistent with his being being employed in lime burning or quarrying, the skills putatively to be taught to Furry Ganges in his indenture. [19]

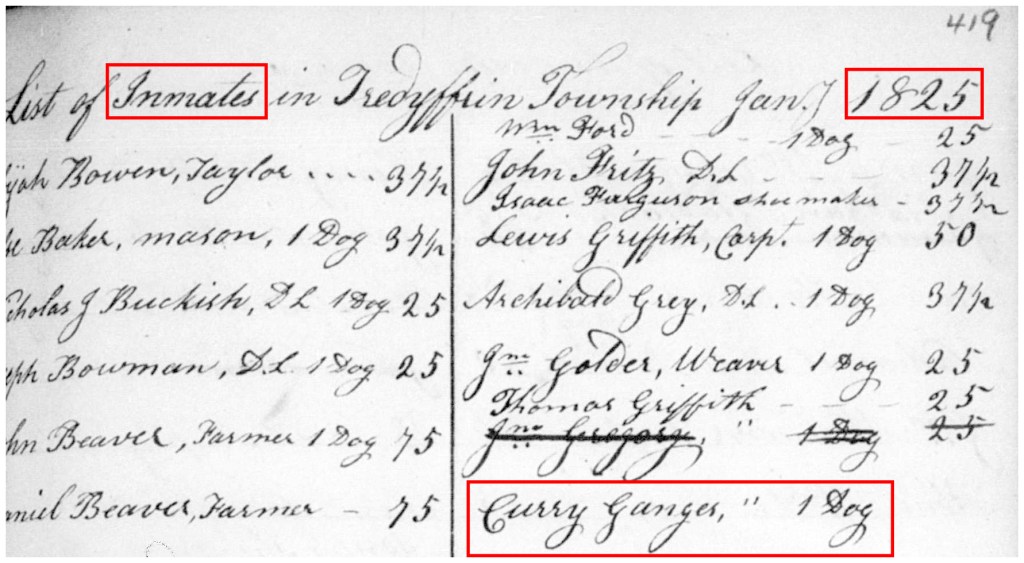

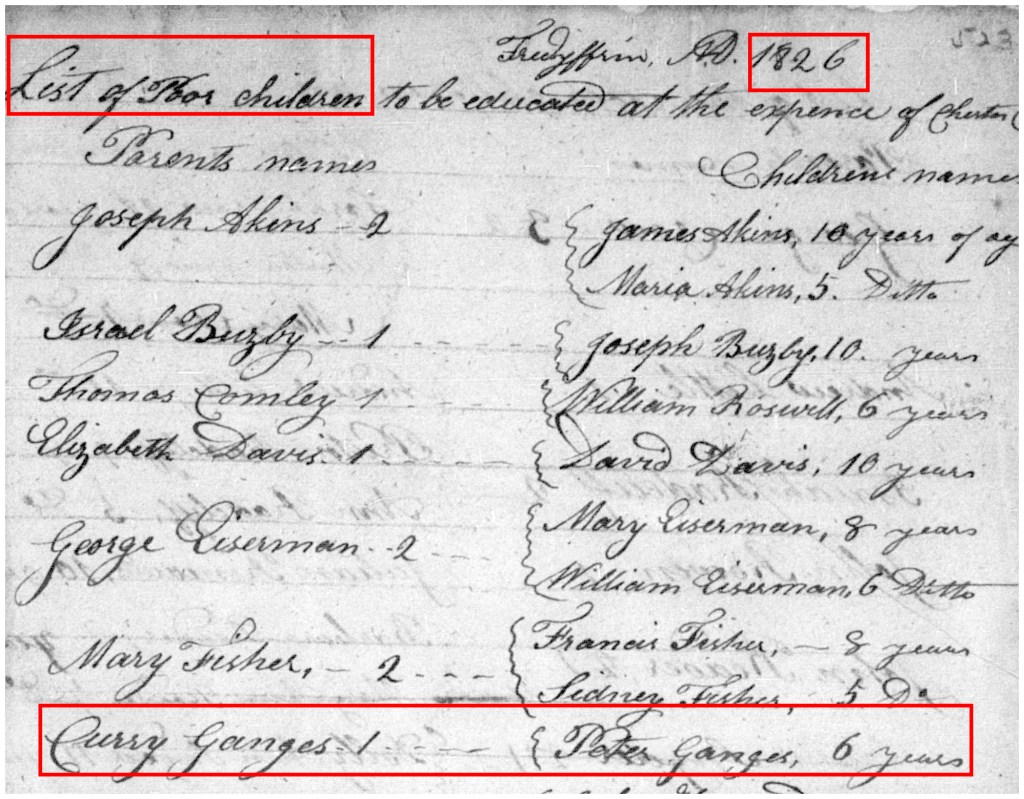

From this point on, the paper trail records Curry’s continuous presence in Tredyffrin. The Chester County tax records list his taxable status as one of inmate, landholder, or parent of poor children for every year from 1825 through 1851. These statuses had distinct meanings. An inmate was a landless married or widowed person, typically a contract laborer. A landholder held the land by lease or deed. A parent of poor children was typically an inmate, but who was listed separately on the taxable schedule because the county forgave their tax obligation if they had children in school (who were listed by name.)[20]

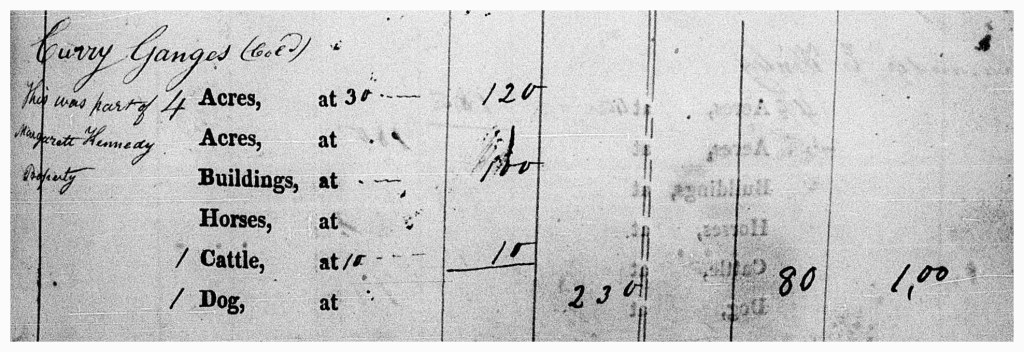

For example, Curry was first listed as an inmate in 1825, being assessed $0.25 for a dog [21]:

while the following year, his son Peter had begun school and Curry was listed as a parent of poor children rather than as an inmate [22]:

For the next eleven years, Curry’s taxable status alternates between inmate and parent of poor children until 1838, when he becomes a landholder, having purchased a four acre property on April 4, 1838, from Margaret Kennedy, widow of Alexander Kennedy, and her children. Consequently, as this 1837 tax record shows, his status is now that of a landholder, and taxed accordingly [23]:

The deed describing Curry’s purchase was duly recorded with the county, the property being “a certain [four acre] messuage lot or piece of land situate in the Township of Tredyffrin”, its price being “six hundred dollars lawful money.” The term messuage means that there was definitely a house already standing on the property at the time of sale. [24] This is confirmed by the 1837 tax record (cited above) and those for the succeeding years, through 185, when the property was sold.

Among the Ganges Africans as a group, land ownership was understandably rare. In the research done to-date, I have found only two or three cases where one of them was able to garner the necessary funds to buy land. In Curry’s case, he was able to secure a mortgage in the amount of $500 from Edwin Moore of Upper Merion, to be repaid within a year. This suggests that Curry was of sufficient character to warrant Moore’s trust. [25]

From an economic standpoint, Curry chose the wrong time to buy, as the United States was suffering the effects of the Panic of 1837, a severe economic depression that lasted well into the mid 1840’s. It may be that Margaret Kennedy and her children chose to sell the property to him to raise cash.

For more than ten years, Curry continues to appear in the tax records as the owner/occupier of the land until his debt appears to have caught up with him. On February 11, 1852, the Common Pleas Court condemned the property for non-payment of the debt to Edwin Moore, and authorized sheriff Davis Bishop to advertise and sell the property at auction [26]:

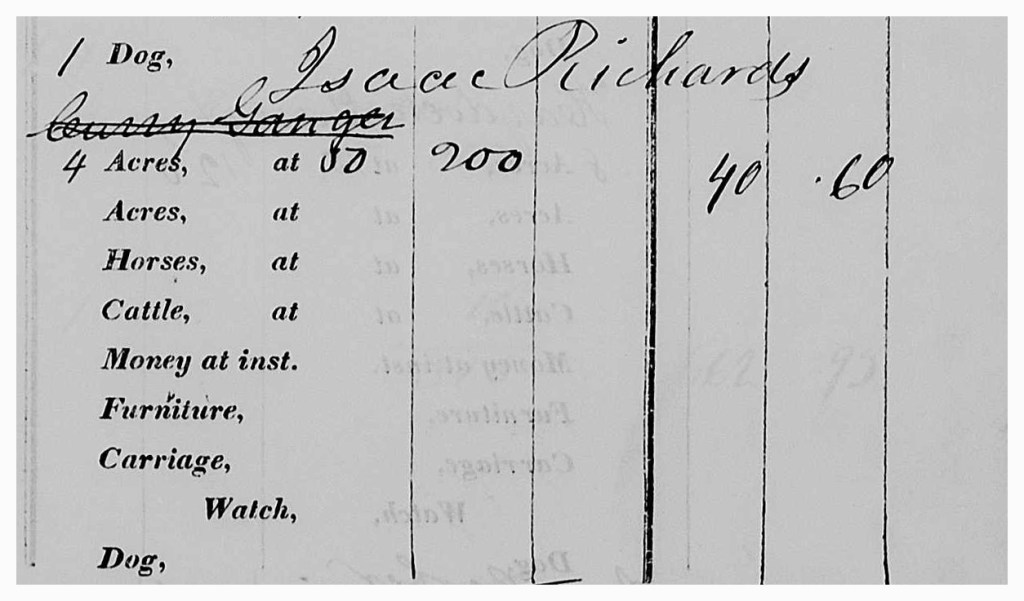

Isaac Richards, a local carpenter, was the high bidder at $650 and the property passed to him on April 29 [27], and Curry’s name was removed from the tax rolls as owner/occupier [28]:

After this, Curry disappears from the tax records but is enumerated as a laborer in the 1857 septennial census of Tredyffrin as a taxable person of color[29]. It is likely he had stayed in the vicinity with his taxes forgiven.

The Fate of the Homestead

After Curry’s homestead was sold in 1852, the property changed hands nearly a dozen times.[31] It’s location is shown on the map above. This is not unusual in and of itself, but the fact that the parcel was only four acres in size may have spared it from the intense development pressures that swept through Tredyffrin after World War II, when large farming parcels were bought up by developers, then subdivided for single family housing with many of the associated farm houses demolished. As described above, the house where Curry lived was “a good stone dwelling house, two stories high, with basement kitchen and cave attached; a good barn, part stone and part frame; stone spring house over an excellent spring of water” Since there was a house on the property when Curry bought it, it’s not clear what role, if any, he may have had in its construction. It IS clear that he lived there, however.

Chester County land records indicate that the bulk of Curry’s lot was not touched until 1961 when, now reduced to 3.2 acres, it was subdivided into roughly 1 acre lots by Robert Bruce Realty. The subdivision plan, shown below, reveals yet another remarkable possibility: that Curry’s house was still standing in 1961. The plan shows a house, barn and spring house, just as described in the 1852 auction advertisement.[32]

Does the house still stand today? It is quite possible, although establishing it will require additional on-site research to evaluate what features still remain.

Final Days

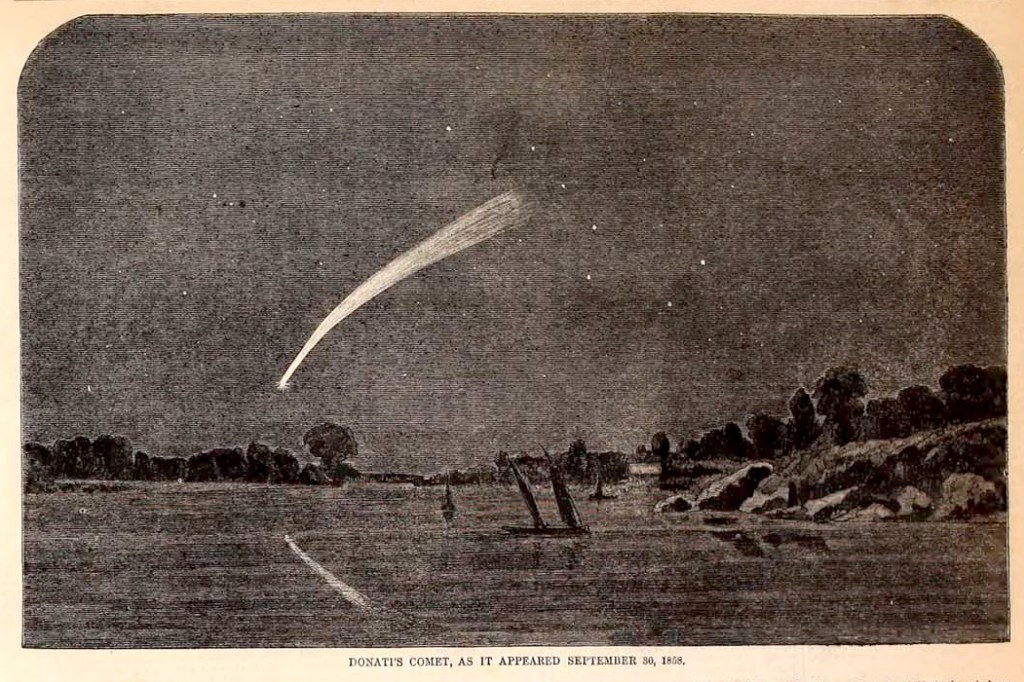

While the nation teetered on the brink of civil war, the summer of 1858 brought celestial wonders. “The Great Comet of 1858” , first observed in May as a faint smudge in the sky by Italian astronomer ?/ Donato had, by August, filled the northern sky with a magnificent cometary display. Like many comets before it, some could see it as an omen of bad things to come. By October, though, with the comet inevitable fading, a southern editorialist grasped the opportunity to scoff at the meaning that abolitionists might assign to it:

Greeley of the “Tribune”, no doubt, sees the fading of this wanderer as he travels southward, a confirmation of his theory of Southern degeneracy, and the fatal influence of the peculiar institution.[34]

Curry probably witnessed the waxing and waning of the comet as well, looking north from an open spot on a hillside looking out over the Great Valley and perhaps saw it as omen of his own passing. He died in late October and was laid to rest at the Valley Friends Meeting on the 21st. Omen or not, the nation continued its descent to the war that would put an end to the institution that had torn Curry Ganges away from his home and family in West Africa so many years before. May he rest in peace.

Notes

[1] The Donohue Funeral Homes and Crematory, “Obituary for Patricia Henry”, online: https://www.donohuefuneralhome.com/obituaries/patricia-henry , accessed 20 June 2023.

[2] Hannah Walker Stephens, Daybook (1857-1864), Entries for 3 June, 19 Oct and 21 Oct 1858, RG5/168, Walker-Stephens Family Papers, Swarthmore Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore, Pa.

[3] Graveyard accounts, 1800-1887, RG2/Ph/V32 4.2. Valley Preparative Meeting Records, QM-Ph-V320. Quaker Meeting Records at Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections and Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College.

[4] Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Deed, Joseph and Ann Lukens to Benjamin Alexander, Deeds 31:264; (digital images, familysearch.org, digital ID 8067242, accessed 17 Jan 2023, Deeds, 1784-1866; index, 1784-1877 > Deed Books 31-32 1814-1816>Image 143). In the parcel description, an adjacent parcel is described as “a lot granted or intended to be granted to Curry Furgander.”

[5] By today’s standards the name Furry might be judged insulting and demeaning. In the18th century it was an uncommon, but not unheard of, first name given to blacks, presumably due to their curly hair. A 1791 Jamaican newspaper ad described a runway man, Furry, as: “short and well-made with remarkably bushy hair.” A number of estate inventories found on ancestry.com also list enslaved individuals named Furry.

[6] Pennsylvania Abolition Society, “Papers, Series IV. Manumissions, indentures, and other legal papers”, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Indenture from Furry Ganges to Jacob Lukens, Box 2 Folder 14. [subsequently, Manumissions and Indentures]. Furry Ganges was indentured for 5 years. The Abolition Society’s practice was to indenture males up to age 21, suggesting that Furry was 16 at the time of his indenture. All the enslaved Africans aboard the Prudent are reasonably assumed to have been born in Africa.

[7] Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Recorder of Deeds, Deeds, 1784-1866; index, 1784-1877; (digital images, familysearch.org, http://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/228409 ). Montgomery County deeds place Jacob Lukens in Philadelphia in 1802(16:434). He is enumerated in Bristol, Bucks County in the 1810 census ( http://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XH2K-JQ4 ) and land records place him in Abington as early as 1809 (27:151) and thereafter. Sales of the three lime quarry lots can be found in 26:211, 26:215 and 26:366.

[8] Detail taken from William E Morris, Map of Montgomery County Pennsylvania from Original Surveys, (Philadelphia, Smith & Wistar, [1849] ); (digital images, loc.gov, digital id: 2012590207, accessed 18 June 2023, URL: https://lccn.loc.gov/2012590207 ).

[9] 1850 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Tredyffrin Township, population schedule, page 33(handwritten), fol. 360 (printed), [subsequently, 1850 U.S. Census, Tredyffrin, Curry Ganges family], line 17, Curry Ganges, black, age 55, born Africa; digital image, Family Search, (familysearch.org: accessed 20 Jan 2023) DGS: 004191087 > Pennsylvania, 1850 federal census : population schedules>Pennsylvania: Chester County (part) Includes West Nottingham, East Nottingham … Tredyffrin, and Charlestown. (NARA Series M432, Roll 764). Image 724; citing National Archives Microfilm publication M432, Roll 764.

[10] Pennsylvania Abolition Society, “Papers, Series IV. Manumissions, indentures, and other legal papers”, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Indenture from Columbus Ganges to Joseph Conard, Box 2 Folder 15; Indenture from Carney Ganges to Richard Thomas, Box 2 Folder 14; Indenture from Furry Ganges to Jacob Lukens, Box 2 Folder 14. [subsequently, Manumissions and Indentures]. All were indentured for 4 or 5 years. The Abolition Society’s practice was to indenture males up to age 21, suggesting that Furry was 16 and Carney and Columbus were 17 or older at the time of their indentures. All the enslaved Africans aboard the Prudent are reasonably assumed to have been born in Africa.

[11] Manumissions and Indentures, Box 2, Folder 15.

Detail from Columbus Ganges’ indenture to Joseph Conard. It reads: “Assigned 5 mo 9 1804 [May 9, 1805] by Consent to Wm Dalby of Kent Co. Delaware.

NB Columbus having Run away. Taken up in Delaware; being Frosted was Put into the poor house”

[12] Richard Thomas Jr., Letter to Richard Thomas Esq, December 9, 1800. Private communication. “We have hired Forton for one month at 5 dollars & have got thee negroes to thresh with him. Carney can thresh pretty well but the other [probably William] is to[sic] lazy.”

[13] Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Deed, Joseph Lukens to Curry Ganges, Deeds 34:163; (digital images, familysearch.org, digital ID 8067242, accessed 16 Jan 2023, Deeds, 1784-1866; index, 1784-1877 > Deed Books 33-34 1816-1818>Image 462).

[14] Montgomery County (Pennsylvania). Board of County Commissioners, Tax list entry for Isaac Alexander, 1816, unp., 4 acres; digital image, Family Search, (familysearch.org: DGS: 008350915, accessed 19 Jun 2023), Tax Lists, 1785-1847> Upper Merion Township 1789-1836, Image 352.) There is a similar entry for 1817, with the annotation “Bros”, suggesting that Isaac and Benjamin, who is listed immediately above with the same annotation, are brothers (Image 371). The lists for 1818 are absent from the collection. Isaac’s name is crossed out in the 1819 entry,(image 390).

[15] Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Deed from Curry Ganges, Isaac and Minty Alexander to John Lyle, Deeds 34:432; (digital images, familysearch.org, digital ID 8067242, accessed 16 Jan 2023, Deeds, 1784-1866; index, 1784-1877 > Deed Books 33-34 1816-1818>Image 597).

[16] Great Valley Baptist Church (Tredyffrin Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania), Church Minutes 25, Dec 1819, “Request for Dismission”; digital image, Family Search, (familysearch.org: DGS: 7903578, accessed 19 Jun 2023), Church records, 1740-1942 [Great Valley Baptist] > Church records 1740-1898 > Image 536).

[17] “Roll Of Emigrants That Have Been Sent To The Colony Of Liberia, Western Africa, By The American Colonization Society And Its Auxiliaries, To September, 1843, &c”, in “Information relative to the operations of the United States squadron on the west coast of Africa, the condition of the American colonies there, and the commerce of the United States therewith,” 28th Congress, 2d. Session, S. Doc. 150, serial 458, page 152.

[18] Ashmun, J, J. H Young, and A Finley. Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the colony of Liberia. [Philadelphia Pa.: A. Finley, 1830] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/96680499/.

[19] 1820 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Tredyffrin Township, population schedule, p. 424 (handwritten), line 26, Curry Ganges; digital image, Family Search, (familysearch.org: accessed 17 Jan 2023) DGS: 005156928> Pennsylvania, 1800 thru 1840 federal census : population schedules> Pennsylvania (1820 census): Adams, Beaver, and Chester Counties (NARA Series M33, Roll 96)>Image 295; citing National Archives Microfilm publication M33, Roll 96. Note that the corresponding index on ancestry.com’s mistakenly characterizes two of the people as enslaved. A careful reading of the original record clearly shows that all those enumerated are free blacks.

[20] For a discussion of the various taxable statuses see the Chester County Archives “18th Century Tax (General Information)” at https://www.chesco.org/DocumentCenter/View/5847/18th-Century-Tax .

[21] Chester County (Pennsylvania). Board of County Commissioners, Tax Transcripts, Tredyffrin Township, “List of Inmates in Tredyffrin Township Jany 1825”; digital images, Family Search (familyeearch.com, accessed 19 Jan 2023, DGS: 008704465>Tax transcripts, 1715-1900> Tax transcripts 1825, Image 419).

[22] Chester County (Pennsylvania). Board of County Commissioners, Tax Transcripts, Tredyffrin Township, “Tredyffrin, A.D. 1826, List of Poor Children to be educated at the expense of Chester County”; digital images Family Search,(familyeearch.com, accessed 19 Jan 2023, DGS: 008704466 >Tax transcripts, 1715-1900> Tax transcripts 1826, Image 523).

[23] Chester County (Pennsylvania). Board of County Commissioners, Tax Transcripts, Tredyffrin Township, “Tredyffrin – Transcript of last trienneal return to levy State, County, Poor and Dog Tax for the year 183[7] at 3 mills in the dollar, on adjusted value”; digital images Family Search,(familyeearch.com, accessed 19 Jan 2023, DGS: 008704482> Tax transcripts, 1715-1900>Tax transcripts 1837, Image 901.

[24] Chester County (Pennsylvania), Recorder of Deeds, Deed, Margaret Kennedy et. al. to Curry Ganges, Deeds P4(vol. 87):592; (digital images, familysearch.org, accessed 20 Jan 2023), DGS: 008083353> Deeds 1688-1903 ; Index to deeds 1688-1922> Deed books, P-4 (v. 87) 1838-1839 Q-4 (v. 88) 1839>Image 313.

[25] Chester County (Pennsylvania), Recorder of Deeds, Mortgage from Edwin Moore to Curry Ganges, Mortgage Book Z, 24:439; (digital images, familysearch.org, accessed 20 Jan 2023), DGS: 008571152 > Mortgage records, 1774-1852; index to mortgages, 1628-1920> Records v. X-22 – Z-24 1833-1842>Image 710.

[26] Davis Bishop, Sheriff, “Property Auction, Tredyffrin Township”, American Republican and Chester County Democrat, West Chester, Penna., 17 Feb, 1852; digital photograph from Newspaper Clipping File, Tredyffrin Township, Chester County History Center, West Chester PA.

[27] Chester County (Pennsylvania), Recorder of Deeds, Deed, Davis Bishop (sheriff) to Isaac Richards, Deeds V5(vol. 118):561; (digital images, familysearch.org, accessed 20 Jan 2023), DGS: 008083353> Deeds 1688-1903 ; Index to deeds 1688-1922> Deed books, V-5 (v. 118) 1854-1855 W-5 (v. 119) 1854>Image 293.)

[28] Chester County (Pennsylvania). Board of County Commissioners, Tax Transcripts, Tredyffrin Township, “Tredyffrin – Transcript of the Triennial Return to levy State, County, Poor and Dog Tax for the year 1852”, digital images Family Search,(familyeearch.com, accessed 19 Jan 2023, DGS: 008705477> Tax transcripts, 1715-1900> Tax transcript: New London – West Chester 1852, Image 438.)

[29] Chester County (Pennsylvania) Assessors, Tredyffrin Septennial Census 1857, Persons of Colour, original at Chester County History Center, West Chester Pa.; digital image, Family Search, (familysearch.org: accessed 21 Jan 2023), DGS: 008188999 > Septennial census for 1857; list of taxable inhabitants taken in 1856 in Chester County, Pennsylvania> Birmingham to Willistown (no. 3649-3706), Image 704.

[30] Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Map of the vicinity of Philadelphia from actual surveys by D.J. Lake and S.N. Beers assisted by F.W. Beers, L.B. Lake & D.G. Beers” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1861. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7dde0070-bb4d-0135-8f2e-003fae5af33f ]

[31] An unofficial deed history of the property is available from the author upon request.

[32] Chester County Recorder of Deeds, “Map Made for Robert Bruce”, (Bryn Mawr, Penna., Yerkes Engineering Inc., 14 Oct 1960), Chester County Plan Book 11, page 20; digital image, Chester County Pennsylvania (chesco.org, accessed 20 June 2023, Property Search>Eagle Web>I Acknowledge>Public Login>Doc# 7565124>View Image.)

[33] “Donati’s Comet as it Appeared September 30, 1858,” Harper’s Weekly Magazine, October 9, 1858, page 653.

[34] Wilmington Journal, Friday, Oct 22, 1858 Wilmington, NC, Vol:15 Page:5.

Beautifully written, with incredible stories of reliance, restoration and growth. Thank you for doing such solid research and bringing this story into our continuous.

LikeLike